- Home

- Leonard S. Marcus

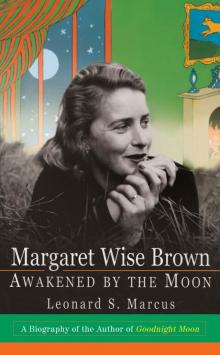

Margaret Wise Brown

Margaret Wise Brown Read online

Dedication

For Amy

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Illustrations

Introduction

Chapter One: “A Wild and Private Place”

Chapter Two: New York Here and Now

Chapter Three: Bank Street and Beyond

Chapter Four: Everywhere and Somewhere

Chapter Five: Other Houses, Other Worlds

Chapter Six: In the Great Green Room

Chapter Seven: “Graver Cadences”

Chapter Eight: “The Fidget Wheels of Time”

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Photo Insert

Also by Leonard S. Marcus

Copyright

About the Publisher

Illustrations

1. Margaret, circa 1917

2. Margaret with her sister Roberta

3. “Tim” and Dana Hall School classmates, 1928

4. Margaret riding at Hollins College

5. Margaret in May Day Court costume, 1932

6. Graduation portrait, Hollins College, 1932

7. Marguerite Capen Hearsey

8. Lucy Sprague Mitchell

9. Children at the City & Country School, New York, 1937

10. Revised typescript page for The Noisy Book

11. Illustration from The Noisy Book

12. Leonard Weisgard

13. Charles Green Shaw

14. Esphyr Slobodkina

15. Michael Strange

16. Michael Strange, 1948

17. Illustration from The Little Island

18. Ursula Nordstrom

19. Garth Williams

20. The Only House

21. Margaret Wise’s Boudoir

22. Jean Chariot, 1951

23. Illustration from The Little Fur Family

24. Clement, Thacher, and Edith Thacher Hurd

25. The “great green room,” from Goodnight Moon

26. Crispin’s Crispian’s house, from Mister Dog

27. Margaret with Crispin’s Crispian

Introduction

I see the moon,

And the moon sees me.

The Oxford Dictionary

of Nursery Rhymes

One never forgot the things she noticed, for she charged them with her own intense feeling. This power of enhancing and ennobling life was felt by all who knew her.

EDMUND WILSON ON,

EDNA ST. VINCENT MILLAY,

The Shores of Light

We speak naturally,” observed Margaret Wise brown, author of Goodnight Moon and other classics of the American nursery, “but spend all our lives trying to write naturally.”1

A contemporary of Ludwig Bemelmans, Robert McCloskey, Virginia Lee Burton, and Dr. Seuss, Margaret Wise Brown was one of the central figures of a period now considered the golden age of the American picture book, the years spanning the post-Depression thirties and the postwar baby boom forties and fifties. Bemelmans and the others began as visual artists who became authors, as it were, in order to have material to illustrate. In contrast, Margaret Wise Brown was a picture-book writer from the start, the first such writer, as Barbara Bader has remarked in her splendid America Picturebooks, “to be recognized in her own right. The first, too, to make the writing of picturebooks an art.”2 Within the children’s book world of that immensely fruitful era, Margaret also occupied a unique place as an inspired author for the very youngest, a group of children for whom few had even thought to write before; and no author before or since has managed so well to shape books that complete what Margaret herself once called the “natural impulse to amuse and to delight and comfort” small children.3

Steeped in the moderns and trained at Lucy Sprague Mitchell’s progressive Bank Street school, she incorporated insights from these and other vital contemporary sources into a tireless personal campaign to make the picture book new. For a time she was a highly innovative juveniles editor, and throughout her career she played impresario to the entire field, taking pleasure in discovering or furthering the careers of illustrators and writers such as Clement and Edith Thacher Hurd, Garth Williams, Leonard Weisgard, Esphyr Slobodkina, Jean Charlot, and Ruth Krauss. It was at Margaret’s urging that Gertrude Stein wrote The World Is Round.

As she became increasingly successful, she used her growing influence to fight for juvenile authors’ and illustrators’ rights in their dealings with publishers. Widely respected by her colleagues, she lived to see her books become extremely popular. Yet Margaret’s success was not without its ambiguities. She remained acutely aware of having made her name in a sector of the literary world that most outside it did not take seriously. Extraordinarily accomplished writer that she was, she never freed herself altogether from the suspicion that to have written for adults would have been a greater achievement.

It’s possible I knew some of Margaret Wise Brown’s books as a child growing up in the early fifties, but if I did I don’t remember. This would not have surprised her at all. Of her own childhood memories of books, Margaret once remarked that it had not then occurred to her that books were written by people; what mattered was whether or not they rang true.

In any case, my work on the present book did not begin as a nostalgic quest for a favorite childhood author. As an undergraduate history major at Yale, I had become curious to know what kinds of books were published for young people during the early nineteenth century, when the American republic was itself still in its formative years. As I was also reading and writing a good deal of poetry, my interest in children’s literature naturally expanded to include the modern picture book, which at its best has much in common with lyric poetry: an ultimate clarity and compactness of expression, a seamless merging of matter and means.

I first became aware of Margaret Wise Brown’s work a few years after graduation, while browsing in a New York bookshop where copies of Goodnight Moon were stacked high on a table. As I read the book for the first time, unaware of the author’s legendary status within her field (or indeed of anything about her) I was forcibly struck by the realization that the quietly compelling words I was saying over in my head were poetry and, what was more, poetry of a kind I prized: accessible but not predictable, emotional but purged of sentiment, vivid but so spare that every word felt necessary. Her words seemed to be rooted in the concrete but touched by an appreciation of the elusive, the paradoxical, the mysterious. There was astonishing tenderness and authority in the voice, and something mythic in it as well. It was as though the author had just now seen the world for the first time, and had chosen to honor it by taking its true measure in words.

I began looking for other books by her and discovered that there were lots of them—over one hundred in all, more than forty of which remained in print over thirty years after publication. Although they varied in overall quality, several seemed memorable to me, many were very good, nearly all were in some sense innovative, and none was without a fresh perception or a jaunty phrase that stuck in the mind. (A train did not go “chug chug” but “picketa-picketa,” while another train went “pocketa-pocketa”; a dog could “belong to himself.”)4

My curiosity was channeled into research—first for a critical essay and a magazine piece, then for this book—and as I proceeded to read the few articles that had been written about her and had my first conversations with people who had known her, I began hearing distinct echoes of the qualities I admired in Margaret’s writings. “She was an original,” more than one of her friends said. She was “mercurial,” “quixotic,” “an experimenter,” “a perfectionist.” Nearly everyone spoke of her in heartfelt superlatives, as

an “irreplaceable” friend, as the “most creative” person they had ever known.5 In more than nine years of research and writing, I have been sustained by a core impression of Margaret Wise Brown as the least complacent of people, as a highly individual personality who time and again bravely tested her limits as a writer and human being.

Some of her experiments in literature and life, I learned, worked better than others. She was a poet of places, a master at shaping (decorating is not the word) her home surroundings into havens that mirrored the emotional warmth and whimsy, and the fascination with the primitive, of her imaginative writings.

However, she seems to have found it exceedingly difficult to meet her peers on equal terms, especially in love. As a lonely but delightfully resourceful child, she had at times to play parent to herself, and she learned the role well, though not without emotional cost, then and later. As an adult, she approached others obliquely, from above and below, with a beguiling mixture of childlike need and proprietary concern for the other person’s welfare. She was forever enlisting collaborators, urging artists and writers to enter her new and largely unexplored field. A publishing colleague wondered, years after her death, if the picture book of all literary forms had not suited her so well precisely because it required the involvement of collaborators.

Over the years of the writing of this book, the first reaction of many people has been, “How did she die? She died so young!” I suppose this is natural given the fact that mention of her death in 1952, “when she was still a young person” (Margaret was forty-two), is just about the only biographical information supplied on the flap of Goodnight Moon, in the note that accompanies the photo of the attractive, open-faced author with a romantic glow.

Nonetheless, for a long time I was puzzled by the sheer intensity of people’s curiosity about this one question, and I have come to believe that it has at least two sources. The first of these is the Romantic myth of the creative artist whose genius flares brilliantly but briefly and is then snuffed out in tragic circumstances. The second is the common premise that children’s literature is a sentimental repository of innocent thoughts and happy endings, and little more than that—how ironic, then, when a children’s author’s own story ends so unhappily.

In some respects, Margaret consciously cast herself in the Romantic poet’s role. She lived flamboyantly, liked to say she dreamt her books (sometimes, apparently, she did). But there was no dark secret to her death; she died of a blood clot following a routine operation. Margaret, always something of a fatalist, had often remarked that becoming a children’s author had been an accident of sorts. Her early death, sad as it was, simply happened.

This point bears emphasis because Margaret’s own approach to children’s literature—and to living—was so bravely unsentimental. Her books have an underlying emotional tautness and honesty about them that is both salutary and rare. They express a clear-eyed respect for the young that both children and adults immediately recognize. Margaret herself could be exasperating. She could also be a generous and charming and affirming friend. But most of all, she never pretended to more knowledge or self-knowledge than was properly hers. She never gave up on growing up. Not least of all for that reason, she was among the most memorable of people.

Chapter One

“A Wild and Private Place”

Every family constructs a mythology of its talents and qualities.

LIONEL TRILLING

In an autobiographical sketch prepared for her publishers, Margaret Wise Brown once described her earliest childhood memories. Among them were images of a “city street with high iron gates, a red brick church at the end of the street and the sound of boats on the river”; a recollection of the “painful shy animal dignity with which a child stretches to conform to a strange adult social politeness”; thoughts about death, dreaming, “mysterious clock time,” and aging; and a “problem of aesthetics I had—why wasn’t an airdale’s [sic] face beautiful, if it was beautiful to me?”1

As a child, a favorite pastime of hers was to make up little tunes, to set poems she composed to old melodies, and to croon traditional songs like “Dixie”—an anthem which beguiled her in part through a misunderstanding: “I thought Dixie Land and Sandy Bottom were two little girls. I envied them and cherished them, as a child does imaginary playmates, and I never understood why Dixie Land kept looking away, but that was just the way she was.”2

As the author of more than fifty books, Margaret later observed that memory, the ultimate source of her creative work, is a “wild and private place,” a place to which “we return truly only by accident”—the writer’s inspiration—“as in a dream or a song,” or by “beaten paths”—the writer’s craft. Whatever the method or the path, she was convinced that “as you write, memory will come out in its true form.”3

The iron gates were those along Milton Street, in the then fashionable section of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, where Robert and Maude Brown had settled as a newly married couple from Kirkwood, Missouri, and where five years later, on May 23, 1910, their second child, Margaret, was born.

Once a bucolic East River village within easy reach of Manhattan, Greenpoint by the turn of the century had been transformed into an “American Birmingham,” a worthy rival to England’s industrial leviathan in the variety and quantity of its manufactures and in the declining quality of its air.4 Robert and Maude Brown, like many of their neighbors, had come to live there largely out of convenience. In 1905, with the promise of a secure future ahead of him in a business that was partly family owned, Robert had moved east to work for the American Manufacturing Company, makers of rope, cordage, and bagging. A short, impatient man, Margaret’s father possessed a shrewdly matter-of-fact view of life and a brilliant mind for mechanical problems. In due course he rose to become his company’s treasurer and vice president.

By 1912, Robert and Maude were the parents of three healthy children, all of them born on Milton Street. Benjamin Gratz, Jr., named for Robert’s father, was nearly two years old when Margaret was born; Roberta, the youngest, arrived when Margaret was not quite two.

It would hardly be noteworthy that an ambitious young company man like Robert Brown was a conservative Republican but for the fact that his own father, the Honorable B. Gratz Brown of Missouri, had been one of the nation’s most progressive political leaders during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras.5 An ardent opponent of slavery, B. Gratz Brown served Missouri as a United States senator and as governor, and in 1872 he ran unsuccessfully for the vice presidency on the Liberal Republican and Democratic tickets, both headed by Horace Greeley.

According to a family anecdote that bears on their relationship, father and son (the boy was not more than nine) were riding one day in an open carriage. Young Robert, having noticed a black person in the street, made some casual remark about “that nigger,” whereupon the elder Brown slapped him hard across the face in a show of his utter contempt for bigotry.6 In later life, Margaret’s father turned petulant at the merest approving reference to any progressive political cause. While Maude Brown deferred completely to Robert in matters of politics, each of their three children reacted differently: mechanically inclined Gratz by wholeheartedly embracing his father’s views and professional interests, intellectually acute Roberta by veering in the opposite direction to become a vigorous Roosevelt Democrat, and Margaret, the family day-dreamer, by becoming more or less apolitical—indifferent to it all.

One senses a tinge of bitterness in Robert Brown’s rebellion. The older of B. Gratz Brown’s nine children—Lily, Mary, Violet, Margaretta—all had memories of life in the heady, privileged circumstances of a governor’s family—a family that could trace its distinguished line of clerics and high government officials back to the days of William of Orange.7 But Robert missed out on the glory days. The governor’s law practice and personal finances had fallen into disarray during his years of crusading public service and remained so at the time of his death in 1885, when Robert was nine. Robert’s mother f

ell ill, was invalided, and died soon afterward. When Robert was ready for college, there weren’t enough funds in the family’s modest inheritance to send him to Princeton or Yale, where past generations of Brown men had studied. His situation was saved only when members of the Gratz branch of the family intervened on his behalf, arranging a first job for him with the American Manufacturing Company in New York. Clinging doggedly to the bit of security thus put in his way, Robert Brown remained with the firm until his retirement.

Three of the Brown aunts must have cut beguiling figures in young Margaret’s imagination, even if she saw them only occasionally. There was an adventurousness, a spirit of fun and extravagance about Lily and Margaretta, both of whom painted and taught art in St. Louis, and about Violet (though she presented a rather more mixed case), which anticipates later descriptions of Margaret herself.

Years later, in a letter to her sister Roberta, Margaret recalled the spectacle of aunts Margaretta and Violet blithely lifting their corsets to show the two girls the scars left from their appendectomies. Another time, Lily and Margaretta ran out of money while touring in Europe and had to cable their prosperous brother in New York for additional funds. (This incident was not soon forgotten in Robert Brown’s household. When Margaret and Roberta wanted to make a similar trip abroad in their mid-twenties, their father was hesitant, fearing that family history might repeat itself.)

Violet Brown moved to Manhattan about the same time that Robert and Maude came East. She had always been fond of her younger brother and may simply have wanted to maintain their close ties. In any case, Violet and Maude never got along. As the self-styled protector of the family name, Violet found fault with both Gratz’s and Roberta’s marriage partners, declaring them “foreigners,” by which she meant that they lacked distinguished backgrounds on a par with that of the Browns. Violet sowed further discord by cultivating a lopsided relationship with her nephew, to the near total exclusion of Margaret and Roberta. (As the sole male heir, Gratz was destined to perpetuate the family name.) Not surprisingly, the girls felt a certain resentment toward her for her assorted inattentions; when, as small children, they decided one day to make some money by selling flowers from the family garden, it was the violets they picked.

Margaret Wise Brown

Margaret Wise Brown